Art review: ECA Graduate Show 2023, Edinburgh College of Art

ECA Graduate Show 2023, Edinburgh College of Art ****

As four-year courses are happily still the norm in higher education in Scotland, the generation of students graduating this year began in 2019 and were badly hit by the disruption of the pandemic. The degree show at Edinburgh College of Art certainly demonstrates their resilience. If there is a bit of anger showing through here and there, that would only be understandable.

There are around 100 students graduating. With the exception of architecture, which is given its own space, the disciplines are all mixed up, which is only to accept reality. The teaching is still divided by departments more or less along the traditional lines of painting, sculpture etc, but there is also intermedia. It morphed out of tapestry and by its title accepts that students are rarely bound by the old parameters.

Advertisement

Hide AdThroughout, the energy is manifest and the Sculpture Court as you enter is a riot. Hanging high above you are a group of enormous, comical heads by Niamh Kroes. Among the work displayed on the floor beneath, Imogen Lee Allen’s installation is a framework hung with various angry statements or exhortations. “Permission to Scream” is burnt fiercely into wood. Others like “Give way to privately educated individuals” are traffic signs.

Also in the Sculpture Court, Billy Brown has an installation of huts on poles against a background of striking black drawings of trees – huts in the woods as a retreat from daily life, apparently. Molly Wickett has an elegant but enigmatic installation of tree branches, soot and shell-like forms, while Tracy McShane has a list of all the world’s endangered languages printed on a great roll of paper in diminishing order of the number of surviving speakers. Hanging from the balcony to the floor, it is depressingly long. Rio Bourke paints, but apparently only on old carpets. They too descend from balcony to floor in a dramatic cascade. Asher Grabber, meanwhile, hangs veils of coloured gauze in a cloud above head height.

Move on into the studios and the range of work is as diverse. I particularly liked Sara Kern’s ingenious reflections on Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus. Its centrepiece is a set of rotating cog wheels made of plaster, a mechanical metaphor for the daily grind that Camus describes. Quite literally the wheels grind themselves to dust, but as they wear out endless spares are on hand to replace them. Camus meets Orwell.

Nearby Lauren MacLean has made a set of images by laser etching onto wood. After a traumatic miscarriage she has imagined the ultrasound scans of twins in the womb. The laser etching burns the wood as the patterns of ultrasound intersect with the patterns of its grain. The result is fierce and very eloquent. Marc Rock’s work is different, but perhaps also angry. It consists principally of a gigantic image on the wall of poor Mrs Jumbo, mother of Dumbo the Flying Elephant, struggling against the cruel ropes as she is tied up by the circus people. In marked contrast, Charlene Scott’s work consisting of delicate, geometric patterns on paper, is small, cool and calm. The lines of drawing read as folds in the paper, but if I understood correctly, they are created from a dye reduction of garden plants. There is more to it too, no doubt, but the results are elegantly restrained.

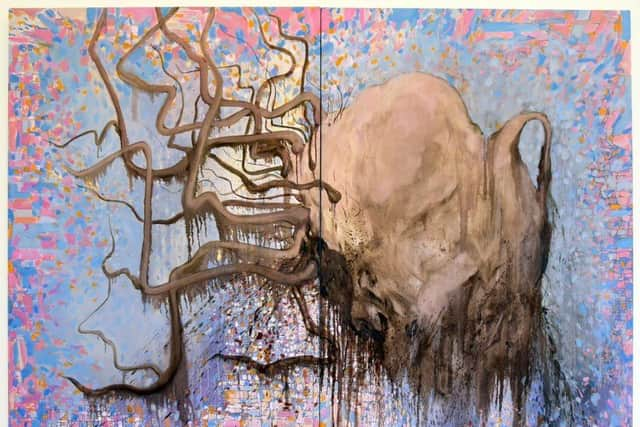

Lara Egan’s three abstract pictures are confidently visceral. They are also relatively big, but Tegan Chaffer paints in miniature. In a corner cupboard – a fixture in the studio – are two tiny domestic interiors made in painted relief inside the lids of jam jars. Paintings nearby are slightly larger, but then a figure has escaped from one of them to sit life-size on the window sill. Megan Owen uses brightly coloured geometric patterns like floor tiles to create complex semi-abstract perspectives of buildings, beautiful places where de Chirico meets Vasarely. Laying out and itemising its traditional tools and materials, Amy McPherson explores the business of painting itself. She then demonstrates the materials in a series of schematic portraits, but she also opens the debate towards the impact of art by reflecting on the choices we make. Lucy-Jane Allen’s small, rather beautiful abstract paintings are accompanied by a robust commentary. “I could have done that!” “Well you didn’t so f*** off!” for instance, and other equally forceful sentiments.

Erical McCracken combines painting and collage in an ingenious way. In an image of a woman lying in bed with a teddy bear at her feet, the face and hands are painted but much of the rest is composed of actual fabrics and a real teddy bear. On the floor, a free-standing image of what might be the same woman in a wheelchair with a companion beside her is a brilliant piece of trompe l’oeil, but made of painted, cut-out cardboard.

Advertisement

Hide AdFelicity Nightingale’s gestural, abstract paintings, all in blue on a black ground, are each accompanied by a poem, presumably also composed by the artist. Alongside some vivid abstract paintings, Jay Darling has one that is completely black. It has also broken out of the confines of its canvas to spill in black dust onto the floor where it is joined mysteriously by what looks like a rusty knight’s helmet.

Tabi Hull’s paintings break out too, as filigree forms of cut paper curl away from the flat canvas. Gabriel Morantin’s figurative paintings in a free neo-classical mode are accomplished and beautiful. One of the most impressive works on show is by Christos Vakirtzis. An emphatic anti-war statement, it has a framed image at its centre with a B52 flying over it, but then the painting bursts its bounds to splash in great sweeps of black right across the wall and onto the floor to look like some huge, angry spider.

Advertisement

Hide AdBethan Frost’s painting is very different in mood. It is a series of beautifully painted, larger than life slices of cucumber that dance joyfully up and across the studio wall. At the centre of Iona Peterson’s show is a copy of a bus shelter on Lewis that sings a song composed by her father. Nearby a little piece of green turf breathes gently, the living earth itself. If you wait for a moment, Tanatsei Gambura’s amazing, small, highly coloured photographic portraits also come to life.

Grace Gerishon evidently has a thing about sea-urchins and has made them into extraordinary sculptures. Some sit on a base on the floor, but another has climbed halfway up the wall. One of the most dramatic installations, however, is by Angeni Perez-Jamieson. It seems to be a volcanic landscape with great lumps of black lava punctuated by bits of volcanic glass dangling above piles of soot.

There is of course much more, but overall it is stunning how this generation has bounced back from the cruel disruption it has suffered. No doubt not all of these graduates will go on to be artists, but whatever they do, the energy and imagination they demonstrate here will surely be invaluable.

In Charles Dickens’s novel Hard Times, Sleary’s circus is a metaphor for the imaginative freedom that is essential to counter the grim world of Gradgrind, eloquently evoked here by Sara Kern. But the Gradgrinds are on the march again. Against them, our art schools are vital champions of that same essential imaginative freedom. As Einstein said, “Knowledge is wonderful, but imagination is even better.”

ECA Graduate Show 2023, Edinburgh College of Art, 2-11 June